A new life in the country

The highs and lows of the first eight months of rural life after relocating, in your thirties, with two young children, six chickens and one old aged dog

Powercuts. Frozen pipes. No central heating in -6°C. Forget about hot water. The snows came blanketing the impassable village roads - no way in, no way out. There was plaster dropping off the walls and a car that exploded whilst we - my husband and I, our two young children and 11 year old dog - were sitting in it. We had become the 'escape to the country' cliche - and we loved it all.

It's safe to say the list of 'disasters' we endured in our first few months of rural life would be enough to put many people off leaving the comfort of suburbia. We encountered them all in the first three months of moving to a small, rural village in North Oxfordshire, near the Northamptonshire and Buckinghamshire borders. We were slap-bang in the middle of three counties - and also in the middle of nowhere. From our large town life, it felt like bliss, even if the nearest takeaway was the fish and chip van that came to the village once a week. With our two young children, aged just four and seven, we made a leap of faith to leave all that we had known in suburban Cheshire to make a new life in the country. So far, it's been what we planned for, all we had imagined and extraordinarily more than we had hoped for.

Over the past few years the creeping dream of country living inched ever closer, tentatively at first but then more intrusively into the daily bustle of the suburban, city-commuting life my husband and I were living. The quiet disillusion of the town, which once had been so promising, was making us softly, soullessly miserable. There were no quiet nights - the main road behind our small garden which had increased in traffic tenfold(+) in the eight years we had called that house home had made sure of that. The constant thrum of vehicles and sirens were the soundtrack to our children's childhoods. We poured our whole selves into curating our home so it gave our daughter and son the childhood we craved for them - between the six foot high fences and cacophony of traffic, we pared back, tended our chickens, grew some food, and spent every minute we could leaving the town we lived in to go walk in the countryside. It was only there, in nature, did we feel connection and calm. It was there we finally felt an absence of motion, where we were free.

Like all good love stories, serendipity played its part. Graduates of the 00s, we had made our way to the city chasing the dream of the careers our degrees had promised but which the financial crash of 2008 denied. Compared to those who had enrolled in graduate schemes a mere three years before us, we faced a desolate job market. I cleaned houses. I babysat children. I became a shopping centre Elf at Christmas and belted out songs over a cheap karaoke machine because this was what minimum wage with a First Class degree looked like. Slowly we found work and a flat we could just about afford, so long as we spent a year living without a television. It was the most formative year of our lives. It taught us that pride is irrelevant when happiness can be found on a Sunday walk along the canal. It also taught us that paths are never linear.

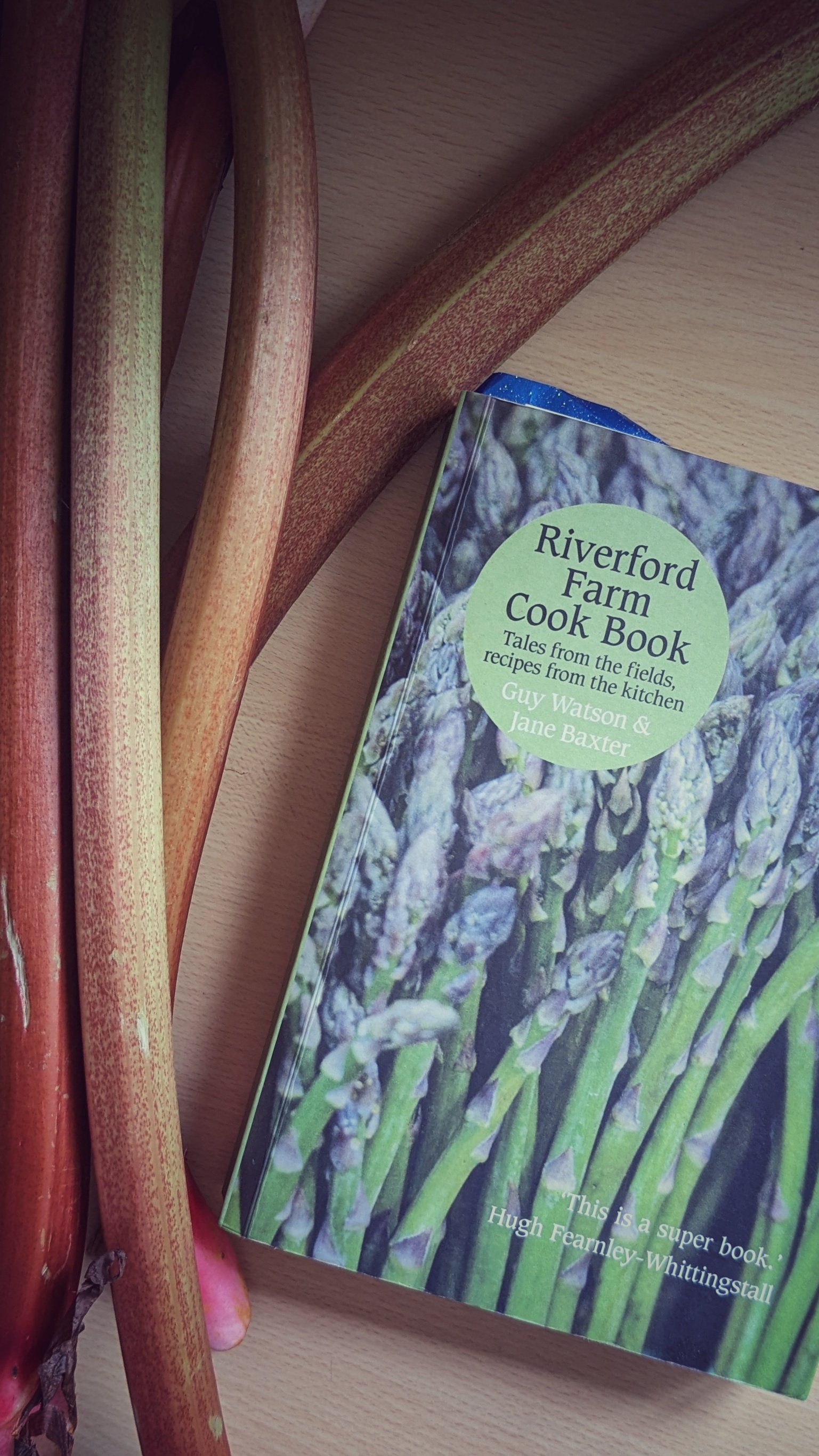

My husband and I are both patient people. We’d happily wait a few years for the right piece of furniture if we can’t afford something, rather than take on debt, even if it means going without in the meantime. That’s how we got our first sofa, in fact: sat on packing crates in the living room of our first rental house, a neighbour spied us through the window, wondered what we were doing and when we explained, he came back the next day and gave us his sofa! (Of course it’s much easier to find secondhand or discounted things now thanks to Facebook Marketplace, Freecycle and Gumtree.) So we prepared to wait until the children were older, our bills were smaller, our mortgage less heavy, to make our escape to country life. We set about researching how to buy land, dreaming up self-build ideas, learning about planning and rainwater harvesting and what was involved in going for an all-out self-sufficiency, small-holding life since we couldn’t seem to find a compromise in our price range. My husband, a designer who works in architecture, had the vision, whereas I held onto the fear. I watched every episode of Ben Fogle’s New Lives in the Wild and New Lives in the Country repeatedly, reading books like John Seymor’s The New Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency (DK, 2019) and even going so far as to learn how to humanely dispatch a chicken. We made lists and plans and held onto that dream as the children started to grow but, as I said, paths are never linear. We did not expect the post-pandemic housing bubble to inflate to epic proportions at the exact moment my husband found a job, in his industry, slap-bang in the middle of the English countryside. Serendipity had just become our best friend.

Driven by our desire to ‘live the change’ (a phrase I hear more and more from others with climate anxiety who are tired of trying to fight the climate emergency), this new life was about so much more than eschewing the bustle of suburban living; it was about finding a place to be connected to the real world - and a place I felt I belonged. I have spent significant portions of my adult life moving across England. If you asked me where I’m from, I don’t think I could tell you but I can say I have not once, until now, lived a rural life. You could say it was the ultimate gamble, except so much of what makes country living worthwhile are the skills and experiences on offer here - if you embrace it, damp and all. I was lucky to be taught how to grow food by my late grandparents, to cook and to repair things and to decorate by my parents, and to have the confidence to try new things even if I fail. You can’t do that if you leave at dawn and return at dusk and spend so much of daily life shuttling from one place to the next which isn’t home. It is clear to me that to make the most of rural life you have to invest in the place you live: pay the milkman, buy from the farm up the hill, use your village hall or hire your neighbour to do your gardening if you need to. Because when the hot water doesn’t work and your kids both need a bath, you’ll soon realise you have the support you craved but never found.

These first eight months have been nothing short of disastrous. We discovered black mold and a concrete render behind the plaster which fell off in sheets. Both our children had accidents, one resulting in surgery, and then, heartbreakingly of all, our lovely little dog died. Even with all this and the astronomical rise in the cost of living, not once have we wanted to quit because, inevitably, something magical happens. Last night, as I closed up the greenhouse, I stopped a moment to watch the bats dance across a glowing evening sky so bright with stars that no one could possibly bemoan the lack of streetlights. Our soundtrack is now made up of tractors and lawnmowers, kids playing on the green or neighbouring dogs hassling ducks in their garden, irritable quacks more comical than any Friday night at the theatre. There are plants for sale outside cottage gates and books to swap in the local church. Someone, at some point in the week, will knock on my door for an onion or a parcel, which inevitably turns into an impromptu cup of coffee and kids playdate, which turns into a walk or dinner or both. This is quiet, unassuming magic. This is the stuff of dreams.

Five tips for embracing rural life

Think of the season ahead: When popping to the shops is a four mile round trip, it pays to be prepared. Keep a larder stocked with essentials. Buy a camping stove. UHT is your friend.

Use what is available: Nothing is waste unless you waste it. Repurpose where you can. Make your own compost. Turn prunings to kindling - your future self will thank you for it when the winter comes.

Be generous: Know your neighbours. Help whenever you can. Kindness costs nothing.

Garden: Grow food for yourself and food for others, whether that’s your friends or the pollinators. Give back to the land you are lucky to enjoy.

Walk: Buy an OS map. Take different routes. Know the land and see how it changes with the seasons - nothing is more grounding than that.